Green tea, the primary type of tea produced in China, mainly comes from the region surrounding the Yangtze River. Its base ingredient is the same plant, Camellia sinensis, as other types of tea; the difference lies in the processing method and the cultivar used. According to the traditional Chinese method, the leaves are fixed in a wok at high temperatures (250–300°C) to prevent oxidation, then rolled, shaped, and dried. The finished tea produces a green-yellow infusion with vegetal aromas and sometimes marine notes.

Iconic Green Teas of China

Chinese green teas exhibit extraordinary diversity, ranging from Dragon Well (Longjing 龍井), shaped into flat leaves, to Jade Snail Spring (Biluochun 碧螺春), crafted into tiny, downy spirals. Another shaping method involves rolling the leaves into pearls; this is Pearl Tea (Zhucha 珠茶), harvested in summer and autumn, also known as Gunpowder, widely distributed in Maghreb countries as the base for mint tea.

The pearl shaping technique is also applied to fine spring harvests, achieving a sublime quality. A remarkable example is “Dew Aroma” (Dishuixiang 滴水香) from the Yellow Mountains (Huangshan 黃山), composed of tiny pearls that unfurl upon infusion, releasing their ineffable freshness. More specifically, this tea is produced in Shexian (歙縣) from a specific cultivar selected and propagated locally by tea growers, who also named it Dishuixiang.

The Cultivars

Even though it is the same species of camellia that forms the basis of all types of tea, the characteristics sought after for green tea (umami flavor, vegetal aromas) can only be achieved from specific cultivars.

Globally, there are two main varieties of tea plants: Camellia sinensis var. sinensis and Camellia sinensis var. assamica. It is the sinensis variety that largely dominates green tea production in East Asia, mainly due to its higher content of catechins and amino acids (see below). In China, within the sinensis variety, over 200 cultivars are dedicated to green tea. Unlike in Japan, where the Yabukita cultivar accounts for about 75% of the cultivated area, no single cultivar truly dominates in China, which partly explains the extraordinary diversity of Chinese green teas. However, some cultivars are very prominent in Chinese green tea regions, and these are the ones we have chosen to present today: Longjing 43, Longjing Changye, Zhongcha 108, Jiukeng, Cuilü, and Dishuixiang.

Although we will not delve into the discussion on whether the cultivars are clonal or not (this could be the subject of another article), it is worth noting that Chinese or Japanese cultivars adapted for green tea production are almost all clonal (i.e., propagated by cuttings). However, there are populations of tea plants known as “quntizhong” (群體種) in China and “zairai” (在来) in Japan, used for green tea production. In China, the term “quntizhong” does not refer to a specific cultivar, but rather to a population of tea plants that is relatively heterogeneous, sometimes consisting of different clones and/or plants from seeds. It is primarily a catch-all category used to label teas from various or unlisted cultivars, but it remains marginal in China’s green tea production.

What Makes a Cultivar Suitable for Green Tea Production?

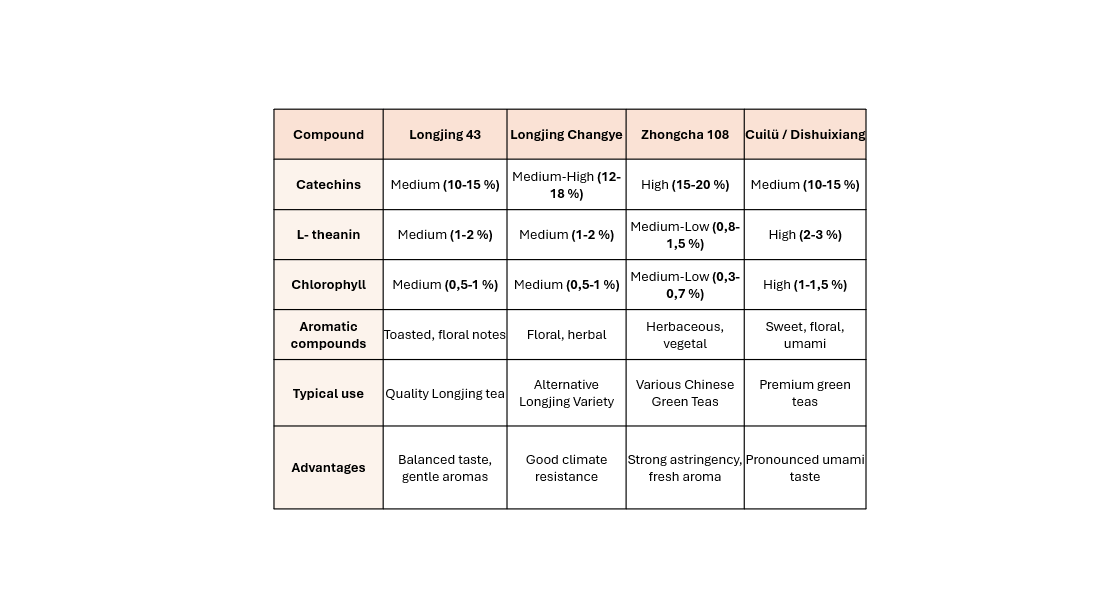

This is primarily related to the high content of catechins and amino acids in its leaves:

- Catechins, recognized antioxidants that are the basis of the health benefits of tea, and especially green tea, provide astringency and bitterness. However, this touch is inseparable from the organoleptic profile of green tea. To remind, the catechins present in the fresh leaf are only slightly degraded during the processing, which allows green tea to be considered richer in antioxidants than other types of tea: in particular, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) remains much more present in green tea, while it is largely degraded in other types of tea.

- Amino acids, notably L-theanine, contribute to the sought-after umami flavor in green teas from East Asia and in gastronomy in general.

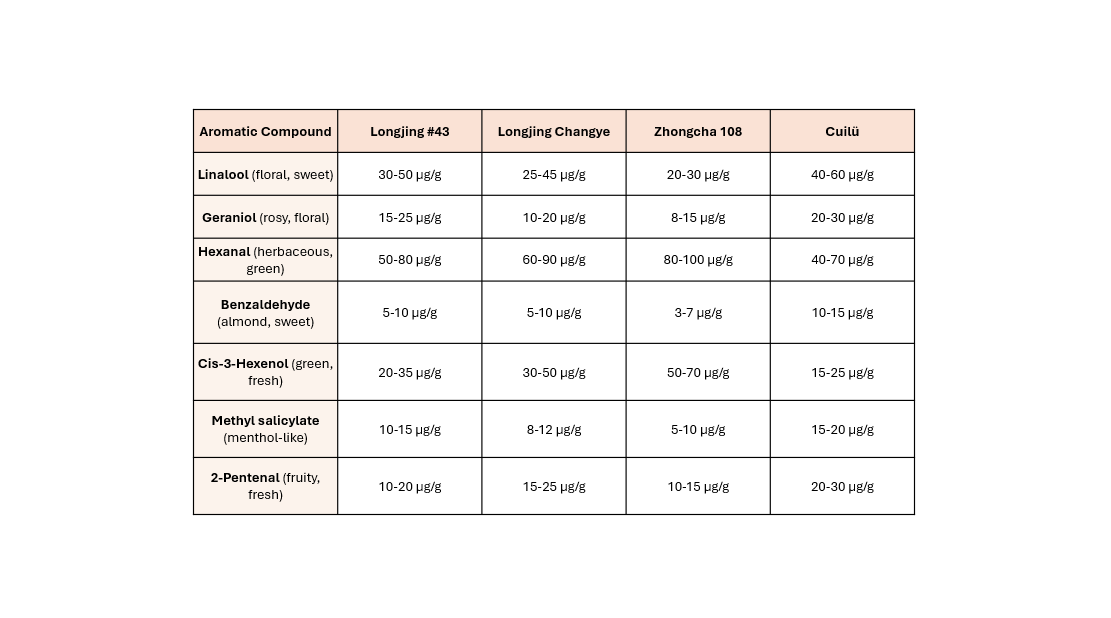

Regarding aromas, a cultivar suitable for green tea will have a relatively high content of aldehydes (e.g., hexanal) and floral alcohols (e.g., linalool, geraniol). On the other hand, it will be relatively poor in heavy terpenes (e.g., myrcene, ocimene) which bring spicy and woody flavors, potentially altering the freshness and delicacy characteristic of the green teas we enjoy.

5 Chinese Cultivars

We present here 5 Chinese cultivars for green tea, all originating from the lower Yangtze River valley. We have experimented with all of them in Brittany and achieved very promising results. Compared to our Breton cultivar, Trévarez, which is also very suitable for green tea, it appears that these cultivars have a significantly higher productivity.

As for the organoleptic qualities, nothing is settled: the Breton cultivar Trévarez sets the bar very high. It will be up to our customers to express their preference once they have access to a wide range of mono-cultivar green teas… and also up to us to find the processing parameters that will reveal the quintessence of each cultivar.

Jiukeng 鳩坑

It is the “ancient variety” of green teas from the provinces of Zhejiang and Anhui; Jiukeng is the name of a small village located along the Xin’an River (新安江), which originates in the Yellow Mountains and then flows down to Hangzhou.

It is likely that seed gardens were established based on a non-clonal population of local plants with similar characteristics. The seeds from these crosses allowed for the reproduction of the general traits of the mother plants. This makes it one of the very rare green tea cultivars that can be reproduced by seed; however, over the past few decades, the best plants from these seeds have been selected and propagated by cutting to address the issue of plant variability.

This cultivar can be used for both flat-leaf teas (such as Longjing type) or twisted-leaf teas (such as Maofeng type). It is renowned for its great aromatic complexity. However, its cultivation has become limited with the emergence of more productive cultivars in recent decades, notably Longjing 43, Longjing Changye, and Zhongcha 108, as described below.

Longjing 43 龍井43

Selected in the 1960s-1970s by the Institute of Agronomy of China for the production of green tea with flat leaves, it was recognized as a “National Cultivar” in 1987 and then propagated across many regions of China; it is used almost exclusively for green tea.

Its leaves are medium-sized, fine, and tender, with a rather light and shiny color. It is adapted to temperate climates. Early in the season, the harvest starts in mid-March in Hangzhou, and one month later in Brittany. It is considered to be quite resistant to diseases but somewhat sensitive to insects; we have not observed any particular issues in Brittany.

The green teas made with this cultivar are considered to have a smooth and soft texture in the mouth, with notes of roasted chestnut and gentle vegetal flavors, and less bitterness than the fast-growing cultivars.

Longjing Changye 龍井長葉

Developed by the same institute as Longjing 43, and labeled in 1994, it is quite similar but has a more upright growth habit and elongated leaves. It is considered to be more resistant to drought and diseases.

Zhongcha 108 中茶

Labeled in 2010, it is one of the most recognized cultivars developed by the Institute of Agronomy of China. Obtained through genetic mutation of Longjing 43, it is even more early-maturing and resistant to cold and drought. The appearance of the leaves is quite similar; however, it is a champion for its catechin content and hexanal, which gives it a pronounced astringency and bitterness, balanced by very lively herbaceous notes.

Cuilü 翠綠

This small provincial cultivar was developed in the Yellow Mountains region in Shexian. Its upright growth habit, large deep green leaves, and high productivity make it one of our favorite cultivars, and it is wonderfully well acclimatized in Brittany. Along with Trévarez, it is the cultivar we recommend to anyone with a professional project in Brittany. Moreover, it is also excellent for black tea and even oolong tea. The Dishuixiang cultivar has leaves that are nearly identical to those of Cuilü, but we can distinguish it by its more horizontal growth habit at the base.

We will conclude with comparative tables on the chemical composition of the leaves from the different cultivars: this data has been compiled from reference works on Chinese cultivars, including 中国茶树品种志 (Chinese Tea Tree Varieties) by Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers (2001) and 中国无性系茶树品种志 (Clonal Tea Tree Varieties of China) by Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers (2014). These data have been partially reproduced on the portal of the International Camellia Society https://camellia.iflora.cn/Home/Index. However, they should be considered with caution, as these contents also depend on the terroir, cultivation methods, harvest season, and the type of leaves picked.